Australia was seen as a world leader in gun control

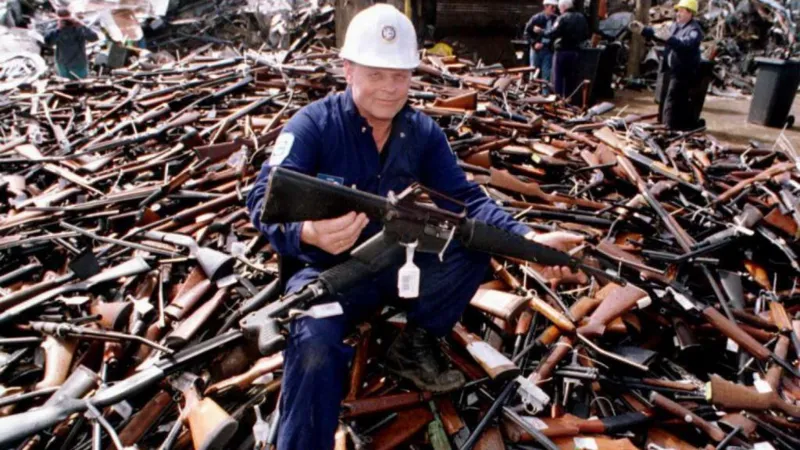

Hundreds of thousands of firearms were surrendered across Australia during the nation’s last major government buyback. Nearly three decades later, the legacy of that moment is once again under scrutiny.

It was a quiet Sunday afternoon in April 1996 when a lone gunman armed with semi-automatic weapons opened fire in the Tasmanian tourist town of Port Arthur, killing 35 people. The massacre shocked Australia to its core and triggered one of the most far-reaching gun law overhauls in the world.

For many Australians, that era has long felt consigned to history.

But Sunday’s deadly attack at Bondi Beach, which left 15 people dead, has reopened old wounds and reignited a national debate thought by some to have been settled.

Few felt the echo of Port Arthur more acutely than Roland Browne, a veteran gun control campaigner whose advocacy helped shape Australia’s post-1996 reforms.

As the Bondi shooting was unfolding roughly an hour’s drive away, Browne, now 66, was hosting fellow campaigners at his Hobart home. They were preparing to lobby government officials for tighter controls on the very type of firearm used by the Port Arthur gunman.

Later that day, news arrived from Sydney.

“There are just so many parallels,” Browne said, speaking from Hobart. He spent childhood summers in Bondi and still has close family ties there. “Both were highly public spaces. Both were places people associate with leisure, tourism and safety.”

The sense of déjà vu was profound. And unsettling.

“It’s sickening,” he said. “And it’s deeply frustrating that calls for stronger public health measures around firearms are so often ignored—until another catastrophe forces the issue.”

A Global Model, With Cracks

For decades, Australia has been held up internationally as a model for gun control. Following Port Arthur, then-prime minister John Howard pushed through sweeping national reforms, including a ban on automatic and semi-automatic rifles and shotguns, mandatory background checks, and a nationwide buyback scheme that led to more than 650,000 firearms being surrendered and destroyed.

The reforms mirrored action taken in the United Kingdom after the Dunblane school massacre in Scotland, which occurred just one month before Port Arthur. Browne remains in contact with families of Dunblane victims—17 people, most of them children aged five and six, were killed.

Yet despite its reputation, Australia’s gun landscape is far from simple.

Gun Ownership at a Historic High

A report released earlier this year by the Australia Institute found that privately owned firearms now exceed four million nationwide—nearly double the figure recorded two decades ago.

That equates to roughly one gun for every seven Australians.

Queensland leads the country in total registered firearms, followed by New South Wales and Victoria. Tasmania and the Northern Territory, however, have the highest per-capita gun ownership.

The findings also challenge the assumption that firearms are primarily a rural phenomenon. In New South Wales, one in three registered guns is located in major metropolitan areas.

While population growth has partly driven the increase, the report highlights a more troubling trend: guns are concentrated in fewer hands. On average, each licence holder now owns more than four firearms.

That concentration, Browne argues, represents a systemic vulnerability.

Calls for Caps, and Pushback

Only one jurisdiction—Western Australia—currently limits the number of firearms an individual may legally own. Under laws introduced there in March, gun owners can possess between five and ten firearms, depending on licence type and weapon category.

Authorities have confirmed that one of the alleged Bondi attackers, Sajid Akram, owned six registered firearms.

Browne is calling for a nationwide cap of one to three guns per licence holder, depending on circumstances. He believes such limits would reduce both lethality and risk.

Gun lobby groups disagree.

Tom Kenyon, chief executive of the Sporting Shooters Association of Australia, says a numerical cap would have done nothing to prevent the Bondi attack.

“These individuals were radicalised,” Kenyon said. “If they didn’t have guns, they would have found other means.”

He points to the 2016 Bastille Day attack in Nice, where a truck was used to kill 86 people, as evidence that weapons restrictions alone cannot stop violence.

Kenyon also disputes claims about urban gun density, arguing that city-based ownership reflects population distribution and the fact that many metropolitan residents travel elsewhere to hunt.

A Patchwork of Laws

Australia’s gun laws are not uniform. States and territories apply the national framework inconsistently, creating loopholes and contradictions.

In general, applicants must be over 18, pass training and safety courses, and demonstrate a “genuine reason” for owning a firearm. Accepted reasons include farming, pest control, recreational hunting, sport shooting, occupational use and collecting.

Self-defence, notably, is not among them.

Yet exceptions abound. Minors can access firearms under supervision—sometimes from as young as 10. Certain weapons may be banned in one state but legal in another.

Polling by the Australia Institute suggests public sentiment is shifting. Seven in ten Australians now believe gun laws should make firearms harder to access, and nearly two-thirds say current laws need strengthening.

Political Momentum After Bondi

Within hours of the Bondi shooting, New South Wales Premier Chris Minns called for tighter restrictions.

“If you’re not involved in agriculture, why do you need these weapons?” he asked.

Less than a day later, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese convened an emergency meeting of state and territory leaders. By Friday, he announced a new national gun buyback—the first of its scale since 1996.

Other proposals include limiting firearm numbers, ending open-ended licences, making Australian citizenship a requirement for ownership, improving intelligence-sharing during licence assessments, and introducing regular reviews of licence holders.

“People change,” Albanese said. “Circumstances evolve. Radicalisation can happen over time.”

The reforms drew mixed reactions. John Howard himself weighed in, supporting stricter laws but warning against ignoring what he described as rising antisemitism as a root cause of the Bondi attack.

An Unfinished Agenda

One major reform proposed in 1996—a national firearms register—remains incomplete. The database is now expected to be operational by mid-2028, after years of delay.

Only after the 2022 Wieambilla shooting, which killed two police officers and a civilian, did authorities accelerate efforts to create it. The Bondi attack has now pushed the register to the top of the national agenda.

A Tragedy That Reopens the Debate

Mass shootings remain rare in Australia. But gun-related incidents are not. Firearms still surface in domestic disputes, organised crime and gang violence—often through theft, poor storage and illicit resale.

For Browne, the lesson is clear.

“Gun control isn’t just about the weapon,” he said. “It’s about suitability, oversight, storage, technology, and accountability. Like a plane crash, it’s never just one failure.”

After Port Arthur, Australia chose community safety over convenience. Browne believes that commitment must be renewed.

“It’s heartbreaking,” he said, “that it takes a tragedy like this to remind us why those laws mattered in the first place.”